Beyond Lithium-Ion

Today's Li-ion battery technology has changed the way we live. This amazing energy storage device has allowed people to run computers that can transmit data to cell towers and run dozens of applications and yet fit in the palms of our hands. It has also enabled the production of vehicles that can travel over 250 miles in a single charge. Unfortunately, the technology for vehicles is still too expensive for mass market penetration, which could be addressed with a step change in energy density. It is for this reason that the Department of Energy (DOE) Vehicle Technology Office (VTO) puts a significant portion of its budget towards what is referred to as "Beyond Li-ion." Beyond Li-ion envisions the use of lithium metal as the anode in place of graphite. A direct replacement of equivalent capacity would result in a 10-fold reduction in the mass anode active material. To support such an effort, VTO funds several initiatives in batteries research, starting with Enabling Li-metal.

Today's Li-ion battery technology has changed the way we live. This amazing energy storage device has allowed people to run computers that can transmit data to cell towers and run dozens of applications and yet fit in the palms of our hands. It has also enabled the production of vehicles that can travel over 250 miles in a single charge. Unfortunately, the technology for vehicles is still too expensive for mass market penetration, which could be addressed with a step change in energy density. It is for this reason that the Department of Energy (DOE) Vehicle Technology Office (VTO) puts a significant portion of its budget towards what is referred to as "Beyond Li-ion." Beyond Li-ion envisions the use of lithium metal as the anode in place of graphite. A direct replacement of equivalent capacity would result in a 10-fold reduction in the mass anode active material. To support such an effort, VTO funds several initiatives in batteries research, starting with Enabling Li-metal.

DOE Energy Storage Initiatives in Beyond Li-ion

Enabling Li-metal

This initiative focusses on understanding the fundamentals of lithium metal plating and devising ways to prevent dendrite formation and intolerable levels of coulombic inefficiency. Some of the more popular approaches for achieving these goals is the formation of microstructures that allow for the accumulation of lithium without the formation of branches or mossy structures. Also being pursued are solid electrolytes, both organic and inorganic, that physically prevent the growth of dendrites during plating. A third, hopeful approach is the development of a liquid electrolyte that simultaneously promotes smooth deposition and is near completely inert to lithium reduction.

Specific projects at Berkeley Lab (LBNL) include:

- Synthesis and Characterization of Polysulfone-based Copolymer Electrolytes

- Composite Cathode Architecture for Solid State Batteries

Sulfur

Sulfur has a theoretical first charge capacity of over 1675 mAh/g, ten times the capacity for lithium than today's lithium-ion cathodes. The problem with sulfur is that in form soluble lithium-polysulfide components in liquid electrolytes as it is lithiated from sulfur to lithium sulfide. These soluble components can migrate to the anode in the liquid electrolyte resulting in coulombic inefficiency and loss of sulfur. Also, lithium sulfide, which makes up at least 50% of the cells capacity during the last stage of lithiation, is non-soluble and an insulator, both ionic and electronic. Despite these challenges, one immediately sees that the efficiency problem would go away if a suitable solid electrolyte was found for Enabling Li-metal.

Specific Projects at LBNL include:

- Simulations and X-ray Spectroscopy of Li-S Chemistry

- New Electrolytes for Lithium Sulfur Battery

Modeling

The recent advent of high performance computing (HPC) has enabled the ability to use computers far amazingly complex problems requiring thousands of lines of code and thousands of computations. Success in this field, as demonstrated by the Materials Project, among other activities, has demonstrated that we can now design new materials with computers and estimate their properties, such as diffusion of ions, voltage for intercalation, and capacity for ions of any size. Researchers have also shown that in a reasonable amount of time, they can calculate the stability of electrolytes and determine the reaction products. This capability is being supported to find new cathode materials with high voltage, high capacity, and low scarce-metal content and new electrolytes that are compatible with lithium.

Specific projects at LBNL:

- Predicting and Understanding Novel Electrode Materials from First-Principles

- First Principles Calculations of Existing and Novel Electrode Materials

- Design and Synthesis of Model Advanced High-Energy Cathode Materials

- Large-scale ab initio Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Liquid and Solid Electrolyte

Advanced Diagnostics

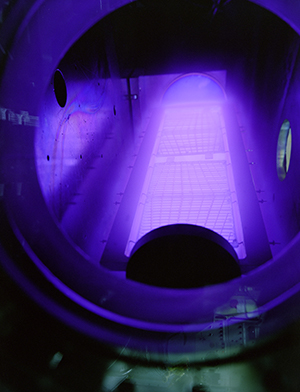

Many of the challenges to finding better materials is fully understanding why the materials we have do not work on the nano and atomic level. For this reason, DOE continuously supports the development of new techniques, for if we can understand what is occurring, perhaps we can change it. The national labs are the home to some of the most powerful experimental resources in the world, from synchrotron light sources to super computer clusters to powerful microscopes to facilities designated specifically to nano science. Finding new ways to use these instruments to understand electrochemical phenomena from an ex situ, in situ, and in operando basis is core to DOE's mission.

Specific projects at LBNL include:

- In-Operando Thermal Diagnostics of Electrochemical Cells

- Interfacial Processes via Near-Field Imaging

Na-ion

A possible bottleneck in the development of massive scale deployment of Li-ion batteries could be the limitation of lithium on the planet. Lithium is the next most expensive element in the battery. Replacing lithium will not be easy as it is the third smallest element and intercalates into many materials. However, sodium is just below it in the periodic table and is far more abundant. There have been several cathode materials discovered that will intercalate sodium to nearly the same degree as lithium but not many anodes. Apparently, sodium does not intercalate into graphite nearly to the degree that lithium does. To overcome this obstacle DOE supports a moderate effort in discovering new, high-capacity, low voltage Na-ion anodes. One can easily foresee that the cost of intercalation batteries would drop again if the main ion were sodium and not lithium.

Specific projects at LBNL:

- High Capacity, Low Voltage Titanate Anodes for Sodium Ion Batteries